The Day General Sherman Kidnapped Hundreds of Georgia Women

Written by Robert A. Waters

Had the Confederate States of America won the Civil War, General William T. Sherman would have been executed as a war criminal. God knows he deserved the noose. After committing innumerable atrocities against Southern civilians, he led the Union army’s forcible removal of Native Americans from their lands, murdering thousands of Indian women and children. This is the story of one of Sherman’s many needless barbarities against innocent Southern women.

Mary Deborah Petite, in her book, The Women Will Howl: The Union Army Capture of Roswell and New Manchester, Georgia, and the Forced Relocation of Mill Workers, writes: “In July 1864, Union General William T. Sherman ordered the arrest and deportation of hundreds of women and children who worked in the cotton mills in Roswell, Georgia. Torn from their homes and transported hundreds of miles away to Northern soil, these helpless victims were forced to fend for themselves in towns overrun by refugees where food was scarce and jobs were few. These women and children were not war criminals nor did they pose a serious threat to the Union army. Nevertheless, they were charged with treason for working in mills that supplied cloth for the Confederate government, jobs which provided their only means of support.”

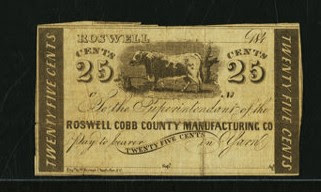

None of the women owned slaves. Far from it. They barely survived on the meager wages they earned working 14 hours a day six days a week. They weren’t even paid in real money, but scrip that had to be cashed in at the company store. Caught up in a war they did not make, the mill women did what they needed to do to survive.

Roswell King, a Connecticut Yankee, was a businessman and slaveholder. In addition to having hundreds of black slaves to look after his many land holdings, he hired about four hundred employees, mostly white women, to work in his cotton mill, the Roswell Manufacturing Company. He became wealthy producing wool and selling it to northern merchants. King built a “colony” around his factory which he named Roswell. There he enjoyed a good life. (Many slave-owners living in Roswell were northern friends of Roswell King whom he had persuaded to move south.)Petite writes that “although far removed from the early battles, the Roswell…mills made a significant contribution to the Confederate war effort by supplying the Rebel armies with sheeting, tent cloth, rope and wool for uniforms.”

As he invaded Georgia, Petite writes that Sherman concluded “it was time to bring the full burden of the war to those who wore neither uniforms nor shouldered guns: the women, the children, the old men, the young boys, the sick and infirm. Although strict orders forbade unauthorized pillaging and plundering, many unarmed defenseless women, young and old, rich and poor, plantation mistress and millworker alike, would suffer cruelly at the hands of Yankee invaders.” Documents from the Union army reveal that hundreds of Southern women were raped by soldiers in the Union army. (There were more than 350 trials of Northern soldiers for rape.) This was likely only the tip of a massive iceberg as many women understood that reporting a rape would likely not be taken seriously by an invading army. Also, rape at the time was seen as a shameful thing, so few women spoke publicly of being sexually assaulted. Black women of the South, some former slaves, some free, were also raped with impunity by Union soldiers.

On July 6, 1864, with many of the Roswell elite having fled to safer climes, Brigadier General Kenner Garrard arrived with his Army of the Cumberland. The next day he sent a detailed report to General Sherman explaining that “Roswell is a very pretty factory town of about four thousand inhabitants…” Nevertheless, Garrard burnt the Roswell Manufacturing Company and other mills to the ground. Hundreds of female employees stood in stunned silence, watching their livelihood crinkle into ashes and rise with black smoke into the sky. Nearby New Manchester also had its factories burned to the ground.

But the worst was yet to come.

On July 7, Sherman sent the following note to Garrard: “I repeat my orders that you arrest all people, male and female, connected with those factories, no matter what the clamor, and let them foot it, under guard, to Marietta, whence I will send them by car to the North…”

The day before the women were to be sent to Marietta, Garrard doled out whiskey to the troops so they could celebrate the burning of the mills. As the Union soldiers drank, they became rowdy, leading to numerous attacks on the mill women. After a day of pillage and rape, the crimes were hushed up by authorities and the assaults never officially acknowledged.

Adeline Buice, six months pregnant with her fifth child, was one of those employees who watched the Roswell Manufacturing Company mill burn. Nine-year-old Synthia Catherine Stewart, stood with her mother as the world caved in on her. Another child, Lucinda Wood, watched the mill go up in flames.

More than 400 women--possibly as many as 1,000--and the few men who worked as supervisors were loaded on to 50 wagons and transported to Marietta, about thirty miles away. (Some women brought their children or infirm parents.) There they were forced into baggage cars for the trip north. Some died en route. Pregnant women had miscarriages, young children deprived of proper care perished, and elderly women and men passed away.

The train stopped briefly in Nashville, then chugged on to Louisville, Kentucky. At least 170 women were dropped off there. Others landed in Indiana. Petite writes: “Put ashore at Evansville, New Albany, and Jeffersonville without food, money or provisions, the mill workers found themselves at the mercy of the local citizens who were ill-equipped to handle the arrival of hundreds of impoverished refugees.”

In Louisville, a “refugee committee” attempted to help the Southern women, but had little monetary backing from locals. Many of the mill workers stayed in barracks, suffering from wounds, illness and “depression.” Some died, and a group of children were alleged to have been taken by a religious order in Bardstown and never seen again. Eventually, some of the women obtained jobs at factories in Louisville. Others married local men, but most disappeared into the mists of history.

When Northern newspaper editors learned of Sherman’s scheme to ship hundreds of refugees to random cities above the Mason-Dixon Line, they howled in disbelief. The Louisville Daily Journal likely spoke for most Kentuckians when it questioned the reasoning behind the move: “Why they should be sent here to be transferred north is more than we can understand.”

The Cincinnati Daily Commercial wryly noted that the capture of hundreds of mill women was “certainly a novel one in the history of wars…” The Harrisburg Patriot and Union in Pennsylvania opined that “it is hardly conceivable that an officer (i.e., General Sherman) bearing commission of Major General should have so far forgotten the commonest dictates of decency and humanity…as to drive four hundred penniless girls hundreds of miles away from their homes and friends to seek their livelihood amid strange and hostile people.”

The other cities encountered the same problems as Louisville. Sickness and death followed, although some were able to obtain jobs at local factories and others married. Most drifted into anonymity.

For those who were determined to return home after the war ended, it would be a harrowing trip.

Lucinda Wood and her sisters encountered tragedy as they rode the train to Louisville when their mother and grandmother died. Since their father had perished the year before, they were left as orphans. They remained at the refugee hospital until they found work in a factory. Lucinda was a pretty girl and it didn’t take long for James Shelly to come calling. The two married in 1866 and later moved to Illinois. The Yankee weather did not suit her and Lucinda became deathly ill. She and her husband decided to move to Georgia, thinking the more favorable climate would be good for her.

In 1886, now with eight children and another on the way, Lucinda and James loaded up a wagon and headed south. They traveled during the day and slept at night under the stars, or beneath the wagon if it was raining. Twelve days later, they were in Kentucky. They kept moving south. Once they reached Tennessee, the hills and mountains slowed them down. By now, they were traveling only about 15 miles a day. Finally, nearly three months later, they reached Jasper, Georgia where Lucinda’s uncle lived. There they settled down and raised their children. The tragic trip north always weighed on her mind, and she often told the story.

Adeline Buice ended up in Chicago. She had her baby there, then miraculously met up with her husband who happened to be a prisoner of war in a nearby camp. She had taken her four children with her, and after the war, the family walked home to Georgia. She lived a long life, dying in 1910.Synthia Catherine Stewart made the trip north with her mother and siblings. They ended up in Louisville where they survived in a “refugee house” until her mother found work in a factory. After the war, her father, Walter Washington Stewart, was released from a Yankee prison camp. Learning that his wife and children had been sent to Louisville, he traveled there and found them. Walter worked at a tanning factory just long enough to save enough money for his family to return home. Synthia later married and lived to be 94. Near the end of her life, she related her experiences on tape.

Karma sometimes misses its mark. After the Civil War, General Sherman went on to lead the Union army in exterminating the Indian nation. He later wrote a slobbery memoir and is now one of the most famous Union generals. He became a hero to Northern schoolboys, although he was a hated man to most Southerners for 150 years.

The Women Will Howl is at once a historical account of Roswell, Georgia and defining work on the singular war crime Sherman committed against hundreds of innocent women and children.

No comments:

Post a Comment