The Flag that Wouldn't Burn

By Robert A. Waters

It was just another afternoon in April, just another spring day and another baseball game. The Chicago Cubs, losers extraordinaire for decades, faced the Los Angeles Dodgers at Chavez Ravine stadium. Back in 1976, most games were played in the afternoon, and few were televised. Vin Scully, the famous Dodger radio announcer, called the game that day. The only drama should have been whether the inept Cubs would pull out a victory over the powerhouse team in the west (they didn’t). But this game would make baseball history in another way.

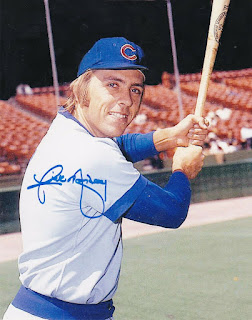

Rick Monday, centerfielder for the Cubs, had been Major League baseball’s first “bonus baby” after a sterling career at Arizona State University. Born in Arkansas and raised in California, Monday served six years in the United States Marine Corps Reserves while playing. He had lost friends in the Vietnam War and visited hospitals where he cried with “torn-up” soldiers and their families.

On this day, a slight breeze rustled in the outfield, something unusual for Dodger Stadium. At the bottom of the 4th inning, Cub pitcher Ken Crosby would face Ted Sizemore. In the outfield, during the break between innings, Monday and left-fielder Jose Cardenal warmed up by throwing the ball to each other.

Monday later recalled, “I don’t know if I heard the crowd first or saw the guys first.” (There were two, an adult and a young teen, and they had jumped over the left field fence and ran onto the field.) Both had longish, scruffy black hair—one was shorter than the other. At first, Monday thought they may be drunk. Or maybe they had run out on a dare. But then an awareness of what was actually occurring burned into him.

“When these two guys ran on the field,” Monday said, “something wasn’t right. And it wasn’t right from the standpoint that one of them had something cradled under his arm. It turned out to be an American flag. They came from the left field corner, then went past Cardenal to shallow left-center field.

“That’s when I saw the flag. They unfurled it as if it was a picnic blanket. They knelt beside it, not to pay homage but to harm it as one of the guys was pulling out of his pocket somewhere a big can of lighter fluid. He began to douse it.”

In the announcer’s booth, Scully cried, “Wait a minute, there’s an animal loose…two of them…all right…I’m not sure what he’s doing out there…it looks like he’s going to burn a flag…”

Monday continued, “So I started to run after them. To this day, I couldn’t tell you what was running through my mind except I was mad. I was angry and it was wrong for a lot of reasons.”

More than 26,000 spectators witnessed the drama unfolding on the field. William Errol Thomas struck a match, but the breeze quickly blew it out. As he lit another, Monday jogged past him, reached down and grabbed the flag. Without looking back, he trotted toward the dugouts. In frustration, one of the wannabe flag burners threw the can of lighter fluid at Monday. Reaching the Dodger dugout, he handed the flag to Dodger pitcher Doug Rau.

Scully exclaimed, “…Rick Monday runs and takes [the flag] away from him. I think the guy was going to set fire to the American flag. Can you imagine that?”

Suddenly, the crowd began to cheer. Then, as Monday recalled, “Everybody in the stands started singing ‘God Bless America.’ I was stunned. I stood there and got chills.”

Security officers quickly arrested Thomas and his teenaged son. The father was later sentenced to 3 days in jail or a fine of $60. His son was never charged. Thomas spent three days in jail, then was released and vanished into the mists of history. Some writers speculated that Thomas was native American and was protesting the history of Indian “persecution.” Others wrote that his wife had been locked in a mental institution against her will, and Thomas hoped to bring attention to that alleged injustice.

James Roark, a photographer for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, was later nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for his picture of Monday sprinting away with the flag.

Since the game had not been televised, it was thought that no video existed of the incident. Then, eight years later, a Super 8 film showing the whole event surfaced. (A fan, whose name I haven’t been able to locate, had taped it.)

Today, Monday is more recognizable for this incident than for his excellent 19-year baseball career. The flag was given to him as a keepsake. He once said he’d been offered a million dollars for it, but it is not for sale. The former Cub later played for the Dodgers and became an announcer for the LA team. He now lives with his wife in Vero Beach, Florida. After his home was damaged by a hurricane, Monday moved the flag to a safety deposit box.

NOTE: The sad tale of James Roark, the man who took the famous

photograph of Monday sprinting away with the undamaged flag, is a story in

itself. The Examiner folded soon after this incident and Roark was never

the same. He began drinking and wandered about the country for several years.

He landed jobs in various restaurants, sometimes as a dishwasher, other times

as a cook, but lost most because of his alcoholism. One night in Portland,

Oregon, as he left Poor Richard's Restaurant to take the bus home from work, he was robbed by four thugs who

beat him to death. Roark was 49. The killers got less than $2.00 and a bus

ticket.