No Room in her Life for Georgie

By Robert A. Waters

Be warned in advance--this story is disturbing.

On a bitterly cold afternoon in 1911, Edith Gibeau Melber visited an apothecary in Schenectady, New York. There she purchased a small bottle of carbolic acid, also known as phenol. Attractive and personable (when she wished to be), Edith had been widowed five years earlier. Her husband, George, had worked as a machinist for General Electric Company. After squandering the $2,500 life insurance she received, she began placing her five-year-old son, Georgie, in various "orphan's homes" in the area. He would remain in each institution for a few weeks, then she would move him to another.

On January 6, Edith picked Georgie up from his great-uncle's home. The Schenectady Gazette reported that "her attitude toward her husband's family was cold and reserved." Charles F. Smith, a musician, and his wife Margaret, relatives on her husband's side of the family, had kept Georgie during the Christmas holidays. They loved the bright, attractive child. Disapproving of Edith's wild, erratic lifestyle, the well-to-do couple attempted to persuade her to let them adopt Georgie. She refused.

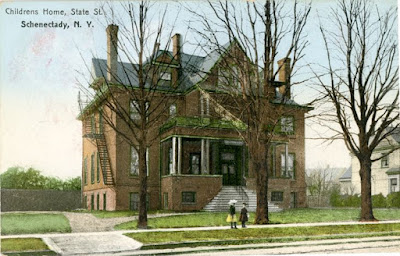

Edith walked with the boy to the Schenectady Children's Home and asked staff to admit him. She had left him there on previous occasions but had neglected to pay the small fee they required. Because of this, the Children's Home turned her down. Georgie wore a brand-new white Buster Brown suit (given to him at Christmas by a couple she had briefly worked for).Edith and her son took a trolley headed toward Albany. Somewhere between Schenectady and the state capitol, they disembarked. In a rural, isolated area, the mother and son began walking aimlessly through the countryside. Edith handed Georgie a bag of chocolate drops which he ate as they trudged along. For the last five years, she had resented the boy and his need for her. Because of him, she found it hard to hold a job and had little social life. Many men wished to date her, but none seemed to want to raise another man's child.

As they walked, Georgie looked up at his mom and asked for something to drink. His mother handed the boy the bottle of carbolic acid. She later told investigators he drank from the bottle. The medicine is corrosive to whatever it touches. As it reached his respiratory tract and his stomach, the child must have been in excruciating pain. (Since no one would willingly drink the acidic poison, detectives surmised that she had forced the drink down the boy's throat--burns on her hands backed up that theory.)

Edith left Georgie lying on the frozen ground, his white suit standing out against the yellowed weeds.

Later that day, Edith was back in Schenectady where she visited her new lover, Howard Kirk, a draftsman for General Electric. On January 12, two days after she'd murdered her son, Kirk drove her to the train depot. She bought a ticket for an early train headed west. "I kissed her goodbye," Kirk told reporters, "and she said, 'I may never see you again.'"

On January 14, a hunter found Georgie's body. The Elmira Star Gazette reported that "Little George Melber's body, badly burned in the face by carbolic acid, frozen stiff by the cold, was found Wednesday afternoon by Harry Sprankland, a hunter, as he followed his dogs across a stretch of frozen swamp-land, about 1,000 feet south of the Schenectady turnpike and just inside the city limits. The autopsy, postponed until Thursday morning to allow the body to thaw out, proved conclusively that death was due to the effect of carbolic acid."

Charles F. Smith was among those who formally identified the sad corpse. Georgie's father's relatives saw that he received a church funeral and was interred at St. Joseph's Cemetery in Schenectady.

Detectives soon arrested Edith and, within an hour, she had confessed.

On March 6, 1911, Edith went on trial. More than a thousand spectators fought to get into the courthouse. While most were there to see her receive justice, a few sympathized with Edith.

On March 16, a twelve-man jury found the mother guilty of second-degree murder. The judge sentenced Edith to a prison term of 20 years to life--at hard labor.

Five years later, Edith fashioned her bedsheet into a noose and hanged herself. Was she unable to live with herself for what she had done? Or was she depressed about her loss of freedom while in prison? We'll never know, but her death brought an end one of the most poignant and senseless cases of murder.

No comments:

Post a Comment