Murder of a “Government Girl”

By Robert A. Waters

By October, 1944, the momentum in World War II had begun to shift to the Allies. Yet, with hundreds of American soldiers still dying every day, the United States War Department continued to hire workers to help defeat the Nazis and Japanese.

Shortly after graduating from high school, Dorothy Berrum passed the civil service exam and left Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin for Washington, D.C. Seventeen-years-old, the newly-hired clerk stood only four feet, six inches tall and weighed just 85 pounds. Despite her appearance, she quickly made friends at Arlington Farms, the War Department dorm where she lived, although friends lamented that the young teenager from the mid-west seemed naïve to the wiles of the city.

She’d been in DC for only three months when she vanished.

A few hours later, in the early morning of October 6, two employees of the East Potomac Park golf club discovered Dorothy’s corpse. She lay face-up in wet grass near the sixth hole. The Washington Evening Star reported that “her face bore bruises and scratches, indicating the victim had put up a fierce struggle before her assailant choked her. Coroner A. Magruder MacDonald said death had been caused by strangulation and that she had been criminally assaulted.” Because of her diminutive size, some reporters described her as “doll-like.”

According to the Washington Daily News, cops “found that the girl had been strangled with her own turban gaudy strip of blue, white, green and purple cloth. The body had been clad in a brown dress covered by a red coat buttoned from top to bottom. Later, it was discovered that the victim’s underclothing was torn. She had been raped, it appeared, then strangled.”

Investigators surveyed the crime scene and, about forty yards away, discovered a belt with a bent buckle. Cops knew it would have been standard issue on a Marine Corps uniform. After collecting the belt for evidence, detectives began attempting to identify the victim. A class ring on her finger provided the clue they needed. The ring came from McDonnell High School and had the initials “D. B.” engraved into it. Cops searched several databases and found a McDonnell High School in Wisconsin. After identifying Dorothy Berrum, they had the task of informing her parents that their daughter had been murdered.

The now-grieving parents had been skeptical all along about Dorothy’s move to the big city, but there was no stopping her. In letters home, she emphasized that she was pleased with her new place in the world.

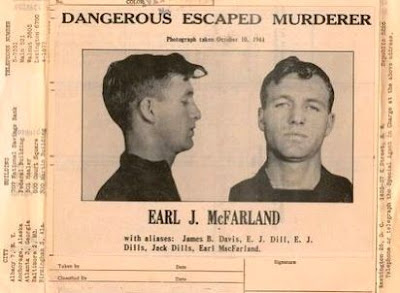

On the evening of October 5, the “government girl,” as

newspapers would soon label her, arranged to meet two girl friends at the

corner of 10th Street and D Street, N.W. When neither friend showed

up, a stranger who identified himself as Earl McFarland struck up a

conversation with Dorothy. Sporting a neatly pressed Marine Corps uniform, he

told her he had fought in Guadalcanal and was on the home front recovering from

malaria. (That was true, but he neglected to tell her he was married, had two

children, had been arrested for several crimes, and had served two years in

prison.)

At 9:15 p.m., they hailed a taxi. She and McFarland got in the back seat, and the driver heard Dorothy tell her companion she was hungry. He asked where she would like to eat and she said, “The Hot Shoppe.” The restaurant, famous locally for its “Mighty Mo,” a triple decker hamburger, and root beer floats, was a few miles away. McFarland told the cabbie, Harold Thomas, to take them in that direction.

The next morning, Thomas saw the girl’s picture on the front page of the newspaper and contacted investigators. The young college-age cab-driver told detectives that after Dorothy had mentioned the Hot Shoppe, the soldier “asked me to have a cigarette and leaned over and whispered in my ear to take them around Hains Point.” Once there, McFarland told him to stop, paid the tab, and exited with Dorothy. Before leaving, Thomas heard the girl ask, “Why are we stopping here?” The cabbie informed investigators that after he let the pair out, he found a switchblade knife in the back seat.Detectives made a beeline to the Marine Corps barracks located in the city. They had three questions for USMC personnel: Who had been out on pass the night of October 5? Who had lost a knife? And who had lost a belt? The answer to each of those questions turned out to be twenty-four-year-old Earl Jackson McFarland, formerly of Knoxville, Tennessee.

While being interrogated, McFarland lied about everything. He claimed the belt was not his. He wasn’t even wearing a belt on October 5, he said. Another soldier at his barracks contradicted McFarland’s claim and produced a photograph taken in a “quickie joint” earlier on the day of the 5th. The picture showed a grinning McFarland wearing the belt. What’s more, investigators saw that the buckle had been bent exactly like the one they had in evidence.

McFarland denied the knife was his. He told police he did not know the girl and had never met her, contradicting the cabdriver’s statement.

And it turned out that even his name, “Earl McFarland,” was an alias. Earl Jack Dills was his real moniker. He had changed names when he enlisted in the military to hide his criminal past.

Detectives suspected McFarland of another murder in the city. Mrs. Margaret Fitzpatrick had been brutally raped and murdered just three weeks before Dorothy Berrum’s corpse was discovered. A friend identified McFarland as the last person to see Margaret alive. He was indicted for that murder but never tried.

As McFarland awaited trial, detectives tracked down the history of the mysterious “switchblade” knife. Marine private John S. Holzberger identified the knife as the one he lent to McFarland while they served in Guadalcanal.

United Press reported that “a Federal Grand Jury today indicted

Pvt. Earl McFarland, 21-year-old Marine veteran of Guadalcanal on three counts—each

punishable by death—in connection with the slaying of 18-year-old Dorothy Berrum.”

Shortly after being housed in the Washington jail, McFarland and another inmate escaped. An investigation showed they had charmed

their way into the guards’ confidence. The website Execution Today

states that during a card game played in one of the guards’ rooms, “they imprisoned

their jailers, nicked their clothes, and cut their way into a ventilation shaft

and out to the roof.” While the other inmate was quickly captured, McFarland

spent eight days on the run before being tracked down in Knoxville.

Meanwhile, newspapers began receiving letters criticizing the military for "snatching" girls from all over the country to work in the dangerous city of Washington. One newspaper editor wrote: "The problems imposed by a tremendous wartime influx of young women have been discussed for months but the discussion has reached a new peak in press, pulpit and among government workers themselves since the tragedy of Dorothy Berrum."

McFarland's trial began on January 8, 1945. Defense attorneys produced three psychiatrists who testified that their client was mentally ill. However, the strategy didn't work. Circumstantial evidence prevailed and the former Marine was convicted and sentenced to death. That sentence was upheld by the U. S. Court of Appeals stating that the evidence “clearly established his guilt.”

He was executed in the electric chair on July 19, 1946.

No comments:

Post a Comment