A Pain with no End

By Robert A. Waters

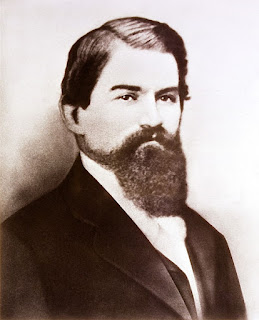

What would it be like to become severely wounded during the last battle of a war that had already ended? Wounded so badly that the chronic pain lasts a lifetime. This happened to John Stith Pemberton and led to the invention of the most popular soft drink in the world: Coca-Cola.

On April 12, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee

surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in

Virginia.

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Boothe assassinated United

States President Abraham Lincoln.

Since most telegraph wires in the war-torn South had been

destroyed, Union Major General James H. Wilson didn’t know either of these

events had occurred. Ordered to occupy the manufacturing town of Columbus,

Georgia, he arrived around 2:00 in the afternoon on April 16. His 15,000 troops

dwarfed those of the defenders of Columbus, which numbered about 3,500 soldiers

and civilian volunteers. Shortly after Wilson arrived, his army attacked.

ExploreSouthernHistory.com states that “by April of 1865,

Columbus was the last surviving industrial city in the South. A major center

for military manufacturing, it was also the home of significant naval

construction facilities where the new ironclad C.S.S. Jackson was

nearing completion.”

Barricades at two bridges across the Chattahoochee River

temporarily kept the invaders at bay. The Confederates blew up Dillingham

Street Bridge to keep the Union army from advancing, but, as the battle began, they spared the 14th Street

Bridge because many of their own soldiers were fighting Yankees on that span.

The battle stormed on into the night, with the Federals finally taking the

city.

Casualties were high, particularly for the Confederates who

fought to the bitter end. One defender, John Stith Pemberton, a Lieutenant

Colonel in the Third Cavalry Battalion of the Georgia State Guard, suffered a

saber wound to his chest during the battle.

“The weapon of choice in the cavalry was the saber. A musket

was incredibly difficult to manage on horseback, especially the muzzle-loading

variety. Most cavalrymen relied on their swords and pistols in battle. The

pistols, which normally fired six shots, quickly became empty and useless in

the midst of an engagement. Pemberton found himself in an equestrian

sword-fight with Union cavalry. According to the closest eyewitness, Pemberton

was both shot and slashed in that encounter. The wound from the saber to his

torso was life-altering. It left a scar that he would carry for the rest of his

life, though he grew weary of talking about it.”

The Pemberton lineage in America dated from 1680 when his

family settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Phineas Pemberton, an ancestor,

served as administrator for William Penn. Since he had been born and raised in

Georgia, John Stith Pemberton fought for the Confederacy. Before the war, when

he was just 19 years old, the young phenom graduated from Reform Medical

College of Georgia in Macon. He later obtained a degree in pharmacy.

After the war, Pemberton continued to live in Columbus with his wife, Ann

Eliza Clifford Lewis, and their son, Charles, in a four-bedroom home. There he set up his lab and began developing the concoction that

would later become Coca-Cola. Pemberton, trying to alleviate the constant torment from his war wound, became addicted to morphine. As his body and mental state

slowly deteriorated, he began trying to find a cure for his habit. (Morphine

addiction became so common among former soldiers the medicine came to be called “Soldier’s

Joy.”)

The Confederate veteran established Pemberton’s Eagle Drug and

Chemical Company on Broad Street in Columbus. There he developed several draughts

which he sold as medicine. For instance, “Globe Flower Cough Syrup” was

described as being “free from opium” and helpful for stopping coughs. He also

opened a wholesale and retail business “selling the raw materials for

pharmaceutical remedies.”

Gardiner writes that “Pemberton’s [newspaper] advertisements

from the era leave no question that he dispensed numerous soft-drink syrups at

his drug store in Columbus. The significant elements in Pemberton’s most famous

formula were the cocoa (coca) leaf and the kola nut. When and where Pemberton

first mixed the world’s most famous formula has been debated.”

He called one of his inventions “French Wine Coca” which was

similar to a French-based drink called “Vin Mariani.” About it, he stated “I am

convinced from actual experiments that coca is the very best substitute for

opium…It supplies the place of that drug, and the patient who will use it as

means of a cure, may deliver himself from the pernicious habit.” It was not well- known at the time that coca (i.e., cocaine) was even more addictive and destructive than morphine.

In 1870, Pemberton moved to Atlanta. There he had some success

selling a perfume called “Sweet Southern Bouquet.” He also served as a trustee

for Atlanta Medical College (now Emory University Medical School). While in Atlanta,

he formed a partnership with other investors.

After a slow start, Pemberton’s original “French Wine Coca”

sold well. He continued to experiment with it, particularly after Atlanta’s city

government banned alcoholic beverages. He removed wine from the formula and

included damiana, said to contain aphrodisiac properties. His drinks were sold

over the counter at various drug stores in Atlanta. Only after he added

carbonation to the formula, and named it Coca-Cola (suggested by his bookkeeper,

Frank Robinson) did he have the final product.

Encyclopedia.com reports that, after an unsuccessful first

year, he used local advertisements to enhance sales: “Soon the product was

spreading across the city, and Pemberton was convinced it was on its way to

national popularity.”

He was right, but he would never see it, having developed stomach

cancer. Suffering from excruciating pain and his seemingly endless addiction to

morphine, “he progressively sold two-thirds of his interest in the company to

other investors, including the transplanted Northern pharmacist Asa G.

Chandler. He retained one-third for his son.”

Encyclopedia.com states that “Pemberton died on August 16,

1888, leaving his wife in a difficult financial situation. A struggle for

control of Coca-Cola followed his death; the financial machinations that

occurred were murky, with rights to both the name Coca-Cola and the formula for

the drink under dispute, and it has never been entirely clear how Asa Candler,

who was responsible for the growth of Coca-Cola in the 1890s, wrested control

of the company from Charles Pemberton and the other investors.”

Tragedy often begets innovation, as it did with John Stith

Pemberton. Had he not been wounded in war, he likely would never have invented

the most popular soft drink in the history of mankind.